Unpromising serpent

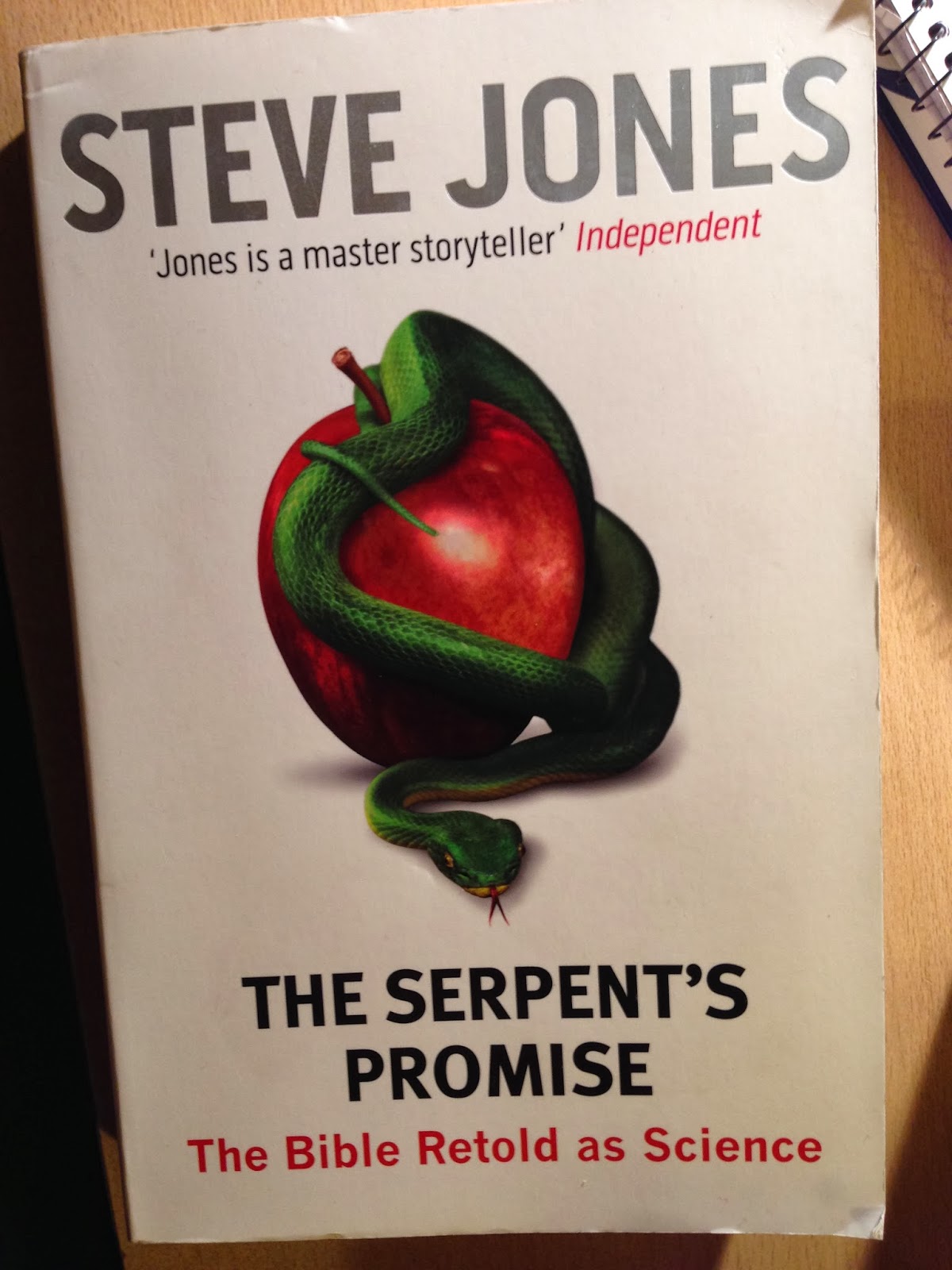

Review of Steve Jones, The

Serpent’s Promise: The Bible Retold as Science (Little, Brown, 2013).

This must surely qualify as one of the worst books I

read last year. That I managed to finish

reading it is itself something of a feat.

Jones purports to be writing something different to the

“Polemical works for and against the power of belief” (p. 4). But this book is nothing if not polemical.

There is a (seriously held) view that science and religion have much that is

complementary and that each can illuminate the other. Jones has dismissed this by page 5. What is more interesting is the reason why

Jones junks this understanding. There is

no exploration of the view, let alone a philosophical account of why it does

not hold water. Rather Jones simply states

“the view that science and doctrine occupy separate, or even complementary,

universes and that each provides an equally valid insight into the world seems

to me unconvincing and is pursued no further here” (p. 5). Jones dismisses a whole school of thought

because it ‘seems to me unconvincing’.

This is at least as doctrinaire as some of the religious positions that

Jones seeks to attack.

But worse than the pick-and-mix doctrinaire approach that

Jones takes to philosophy is his religious illiteracy. Jones makes statements about religion and the

Bible that are simply fatuous. So we are

told that “Genesis was the world’s first biology textbook” (p. 19); Jeremiah

quotes God as “evidence that the fertilised egg has a soul” (p. 137); and that

“Leviticus … is obsessed with hygiene” (pp. 276-277). Any of these statements should be beneath a

sixth-form essay in Biblical studies.

The anecdotal style of the book, means that there is little of

substance, a lot of cheap shots and an overarching smugness that is very

unattractive.

Worst of all is the simplicity of Jones utopian

understanding of history. He tells us

that in the genealogy of ideas, science is the “direct descendant” of the Bible

(p. 3). Jones offers us an account of

progress in which “many dogmas from animism to Scientology have succeeded each

other” (p. 418) and which have ultimately resulted in science. The Jonesian future is a totalitarian vision

of “a single community united by an objective and unambiguous culture whose

logic, language and practices are permanent and universal. It is called

science” (p. 418). Given the way in

which Jones places scientific triumphalism alongside stories from the Bible,

one might expect the tower of Babel to feature here. But the biblical challenge to scientific

hubris is curiously absent.

There are good books, written or yet to be written, on

science and the Bible. There are and will be

books which pose serious challenges to faith, Christian or other, from the

position of science. This book is neither. Don’t waste your time or your money on it.

Comments