Unapologetic: Michael Ramsey Prize Shortlist 4

-->

Of course the very thing that makes this such a

good book is also a limitation. In this

post-Brexit country, we should be more wary of assuming a single common

culture. It is also a very Protestant way

of making emotional sense of Christianity.

However well expressed, the emotional sense of being released from sin

and finding the freedom of being forgiven has deep Lutheran resonance. Nor will

this book address people with the same sharpness in years to come. But none of these limitations mars the force

and the point of Spufford’s book, let alone the enjoyment it provides. This book will date. So read it now! It is a book of the present to be devoured

and enjoyed soon. Enjoy.

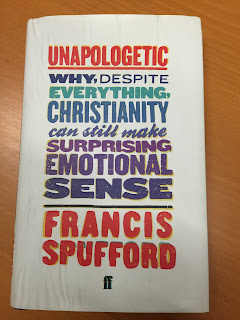

Review of Francis Spufford, Unapologetic: Why, despite everything, Christianity can still make

surprising emotional sense (Faber and Faber, 2012).

This is the only book on the Michael Ramsey Prize shortlist

that I had already read. In the spirit

of the enterprise, I re-read it so that I could review it alongside its fellow

nominees. I enjoyed it as much on the

second read as I had on the first.

This is, quite simply, an excellent book. It is very well written, by turns profound,

insightful, irreverent and funny.

Spufford’s conceit is to write a book to explain why he is weird enough

to go to church. In order to do that, he

offers an account of faith that draws on and speaks to contemporary

culture. There are lots of references to

popular culture in here. Don’t skip the

footnotes, they are where some of his best, funniest and most barbed comments

are to be found. Take this one as an

example: ‘Everyone in England has a church they can go to. In the unlikely event that a heartbroken

Richard Dawkins wants help … there will be someone in North Oxford whose

responsibility it is to offer him an inexpensive digestive biscuit and a cup of

milky tea, and to listen to him for as long as it takes’ (p. 184). Apart from the slight on the clergy’s ability

to make tea, this also demonstrates the ongoing argument that Spufford has with

so-called ‘new atheism,’ and especially with Richard Dawkins. With humour and the occasional barb, Spufford

is keen to demonstrate that there is little new about Dawkins and that Christianity

is actually a supporter of the sciences.

The Church of England, suggests Spufford, is one of the main reasons for

the speed and ease by which Darwin’s ideas were spread and accepted. This leads Spufford to the marvellous

conclusion that ‘If you’re glad Darwin is on the £10 note, hug an Anglican’ (p.

102).

Spufford’s account of sin – ‘the human propensity to fuck

things up’, or ‘HPtFtU’ (pp. 26-27) – is engaging, serious and helpful. It is something that he continues to draw on

throughout the book. It helps Spufford

to make sense of God, Jesus, and, especially, the church in all its idiocy and

damaging reality. Above all, it helps

Spufford to make emotional sense of his faith.

This is not emotion opposed to reason, but it is emphatically not reason

that is divorced from lived faith.

Spufford’s emotional apologetic is one that integrates thinking, story,

and the joys and pains of life. He can

spend a long time working through the significance of an argument with his

wife, and uses this reflection to ground some of his thinking. He is trying to show that ‘The emotions that

sustain religious belief are all, in fact, deeply ordinary and deeply

recognisable to anybody who has ever made their way across the common ground of

human experience as an adult’ (p. 22). I

think he succeeds rather wonderfully.

Comments